Confessions From The Reading Room: A Deep Dive Into Mötley Crüe's Literary Legacy

You've got the look, you've got the style, you've got the attitude, you're a book...

Let me take you back to the Sunset Strip circa 1982, when hairspray hung in the air like a toxic cloud and the sidewalks vibrated with the promise of decibel-defying musical debauchery. Before they conquered stadiums and MTV, Mötley Crüe was just another hungry band fighting for space on marquees alongside Quiet Riot, Ratt, and countless forgotten glam hopefuls. But even then, something about them was different.

I caught them in those early days, fake ID in hand, when you could still get close enough to the stage to dodge Nikki’s sweat and feel the heat from the pyro. Their music hit me as the perfect bastard child of everything dangerous in rock—equal parts punk snarl, glam theatrics, metal heaviness, and pop hooks, all delivered with a middle finger and a knowing wink. The first two albums especially (“Too Fast for Love” and “Shout at the Devil”) captured a band with nothing to lose and everything to prove.

The Rainbow Bar & Grill became my unofficial education in rock anthropology. Between the booths and the bar, I’d occasionally find myself sharing space with Tommy’s manic energy, Vince’s California drawl, Nikki’s calculated intensity, or Mick’s quiet presence. In those days, we didn’t document every celebrity encounter with photographic evidence—partly because we weren’t carrying cameras, but mostly because asking for a picture would have marked you as hopelessly uncool, a tourist in a world where everyone pretended to belong.

Years later in 2007, when I finally interviewed Nikki Sixx and captured the moment with a photo, the irony wasn’t lost on me. By then, both of us had survived the 80s—him more narrowly than most.

My fascination with the Crüe has always been about the contradictions—four drastically different personalities creating something that worked precisely because of their differences, not despite them. When I dive into a band’s story, I want all angles, all perspectives, the Rashomon effect of rock biography—if Kurosawa had been really into Jägermeister and spandex. I did it with KISS (which became one of my most-read Substack pieces), and now I’m turning that same obsessive lens toward the Saints of Los Angeles.

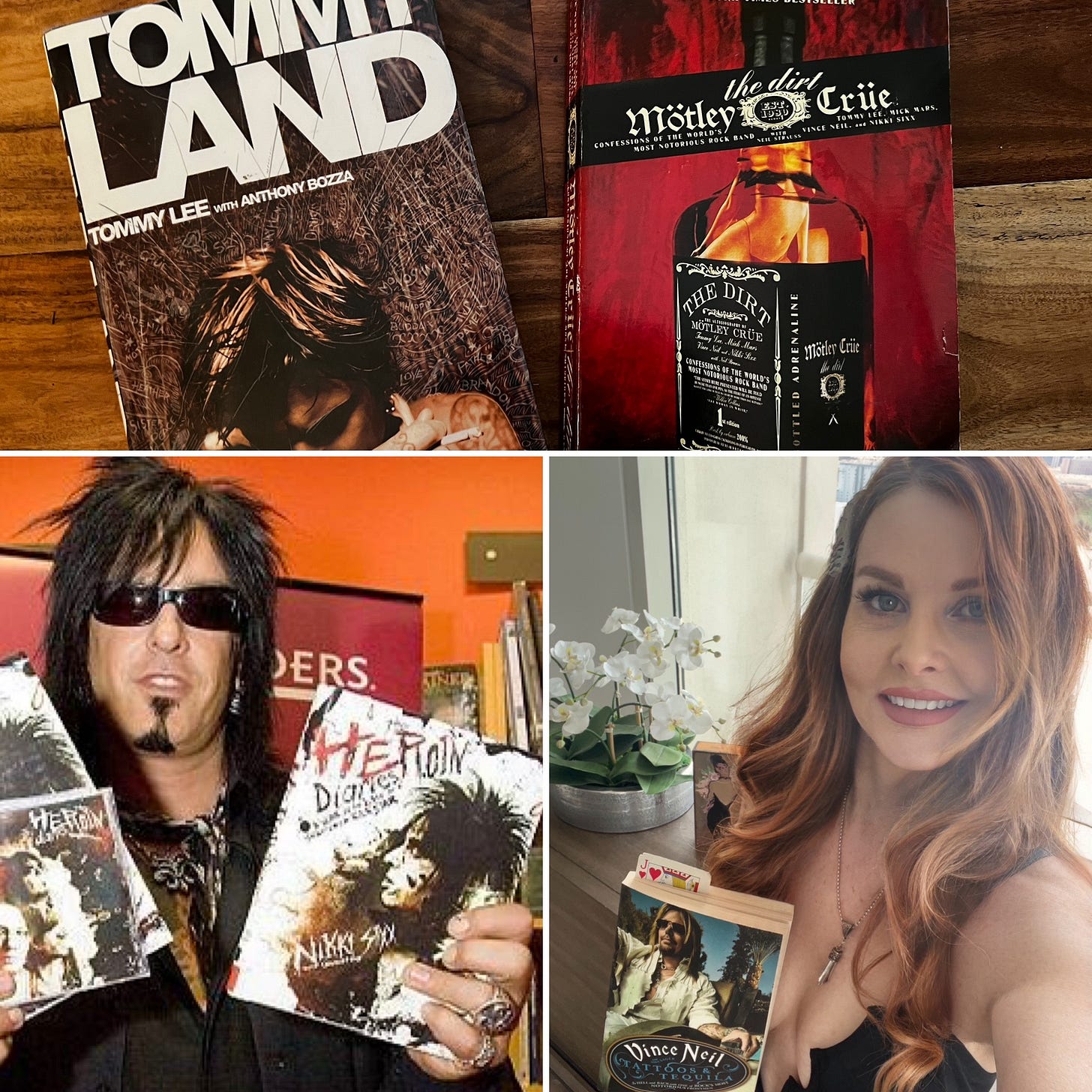

With Netflix’s adaptation of “The Dirt” reigniting my interest (I’ve watched it at least four times) and “Pam & Tommy” offering yet another window into their world a few years back, I finally had the time to revisit their literary output. I’d read “The Dirt” and “The Heroin Diaries” years ago, but recently added “Tommyland” and Vince’s “Tattoos & Tequila” to complete the set, reading them for the first time this year.

What follows is my journey through the bookshelf of America’s most notorious band—four books, four perspectives, and one wild ride through the highest highs and lowest lows of rock stardom. Strap in, keep your hands inside the vehicle at all times, and remember—what happens in Tommyland stays in Tommyland. (Usually because it’s too incriminating to take elsewhere.)

THE DIRT: Where Hair Metal Meets the Confessional Booth

In the sweaty pantheon of rock memoirs, “The Dirt” sits atop the throne like a Viking conqueror, surveying the conquered territories of good taste with a smirk and a raised middle finger. If books had MPAA ratings, this one would require multiple warning labels and possibly a hazmat suit.

Published in 2002 (with Neil Strauss heroically attempting to corral the chaos), “The Dirt” pioneered the “let’s-tell-absolutely-everything” approach that would later become standard in rock autobiographies. The difference? Most bands don’t have quite this much everything to tell.

The oral history format—typically the literary equivalent of a potluck where someone forgot to bring plates—works surprisingly well here, allowing each band member’s distinctive voice to shine through. Nikki’s calculating intellect, Tommy’s puppy-dog enthusiasm, Vince’s breezy detachment, and Mick’s world-weary stoicism create a four-part harmony of decadence that’s more compelling than it has any right to be.

What emerges isn’t just a catalog of hotel rooms destroyed and bodily fluids exchanged (though there’s plenty of that), but a surprisingly nuanced portrait of four deeply damaged individuals who found each other, created something electric, and then proceeded to nearly destroy themselves and everyone around them with remarkable dedication.

The childhood sections reveal trauma that contextualizes (though never excuses) the later behavior. Nikki’s abandonment issues, Tommy’s desperate desire to be loved, Vince’s lack of consequences, and Mick’s physical and emotional pain form the psychological bedrock upon which the Crüe’s particular brand of bedlam was built.

The middle section—chronicling their rise from Sunset Strip outcasts to arena-filling superstars—offers fascinating glimpses into an industry that was stubbornly committed to New Wave while rock allegedly lay dying. Only a 20-year-old intern at Elektra saw what was obvious to anyone with eyes and ears: these guys were going to be massive, mainstream objections be damned.

Throughout it all, Nikki emerges as the band’s dark heart—the songwriter, the visionary, the architect of their sound and image. Dating Lita Ford while crafting anthems of excess, he’s portrayed as the chess master even while descending into heroin addiction that would eventually stop his heart. Twice.

The book doesn’t shy away from the ugliest moments—Vince’s vehicular manslaughter, the casual misogyny, the destruction both of property and relationships. The portraits of their partners (including Heather Locklear and Pamela Anderson) are rendered with about as much depth as you’d expect from men who viewed women primarily as accessories to their rock star personas.

By the end, “The Dirt” transforms from a celebration of excess to a cautionary tale. The final chapters, with their admissions of addiction, loneliness, and emptiness, feel like the inevitable hangover after rock’s longest party. It’s the literary equivalent of waking up in a trashed hotel room, surveying the damage, and wondering if it was worth it.

Re-reading it in 2025, over two decades after its publication, “The Dirt” is both a time capsule and eerily relevant. Before social media made everyone’s worst moments potentially public, these guys were living as if someone was always watching—because someone usually was. They created a reality show before reality shows existed, turning their lives into performance art that was equal parts fascinating and repellent.

For better or worse, “The Dirt” redefined what a rock autobiography could be. Less concerned with artistry than with excess, it remains the gold standard for bands looking to confess their sins without actually repenting. Two decades later, it still shocks, entertains, and occasionally even moves—much like the band itself.

THE HEROIN DIARIES: One Man’s Guided Tour Through His Own Personal Hell

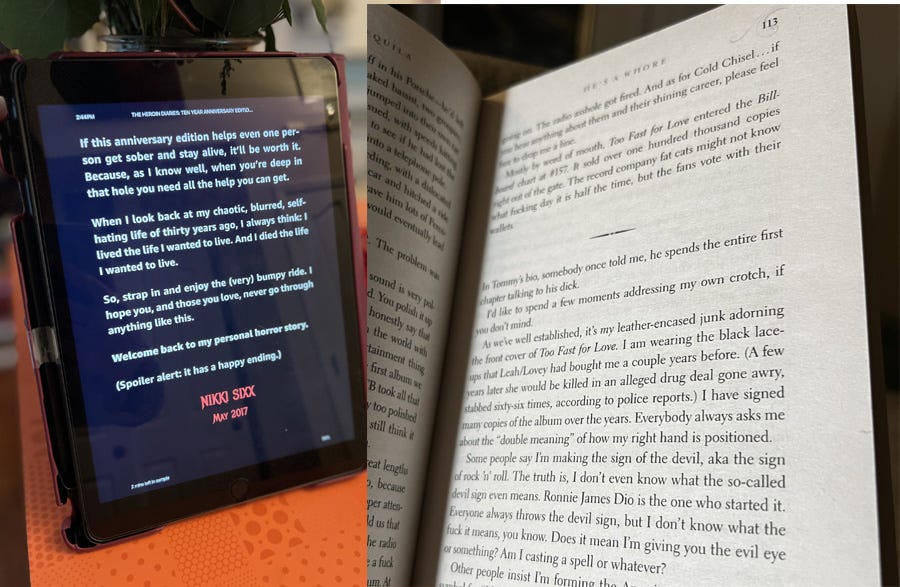

If “The Dirt” was Mötley Crüe’s group confession, “The Heroin Diaries” is Nikki Sixx’s private session with a therapist who nodded off midway through. Published initially in 2007 (with a ten-year anniversary edition in 2017), this chronicle of Sixx’s year-long journey through addiction’s darkest corridors makes “Trainspotting” look like training wheels.

The format is both brilliant and disorienting—actual diary entries from Sixx’s 1987 spiral, interspersed with present-day commentary from the people who witnessed the carnage. It’s like watching a car crash in slow motion while the survivors provide color commentary from the future. The effect is both powerful and occasionally infuriating, but is reined in somewhat by Nikki’s collaborator, Ian Gittins.

What emerges is a portrait of a man who had everything—fame, fortune, creative fulfillment, an endless parade of willing partners—and was still so empty inside that only heroin’s artificial warmth could fill the void. The daily descent into paranoia, isolation, and self-hatred is documented with an unflinching honesty that’s equally admirable and exhausting.

Sixx’s intelligence shines through even at his lowest moments. Between bouts of hiding in closets with shotguns, convinced the “little people” were coming for him, he manages insights about his childhood abandonment issues that would get Freud taking notes. It’s this self-awareness, even in the midst of self-destruction, that makes the book compelling rather than simply voyeuristic.

The guest commentaries provide crucial perspective. Tommy Lee’s bewildered loyalty, management’s frustrated enabling, and various girlfriends’ confused attempts to help create a 360-degree view of addiction rarely captured in memoirs. Vanity’s sections are particularly fascinating—her journey from Prince protégé to fellow addict to evangelical Christian zealot forms its own bizarre subplot worthy of a separate book.

By the midpoint, the repetitive cycle of scoring, shooting up, paranoid delusions, and brief moments of clarity begins to mirror the monotony of addiction itself. This is both the book’s greatest strength and its ultimate weakness—it perfectly captures addiction’s tedious rhythm while occasionally testing the reader’s patience. How many closet-hiding, gun-waving, demon-seeing episodes can one consume before compassion fatigue sets in?

What the book occasionally lacks is broader context. While Sixx rightfully acknowledges his privilege—burning through a million dollars of drug money in a year while maintaining his rock star job—he doesn’t always connect his experience to addiction’s universal truths. The brief mentions of guitarist Robin Crosby’s fate (AIDS, homelessness, death) hint at the darker destiny Sixx narrowly escaped, but these parallels feel underdeveloped.

Many years after the events it describes, “The Heroin Diaries” remains a harrowing document of addiction’s gravitational pull. Sixx, the bassist who kept perfect time for America’s most notorious band, chronicled his own journey to rock bottom with the same meticulous attention to detail he brought to his music.

The happy ending—Sixx’s survival, sobriety, and transformation into a multimedia entrepreneur and addiction awareness advocate—provides necessary redemption to what would otherwise be an unbearably dark journey. Unlike many rock memoirs that glorify excess while nominally condemning it, “The Heroin Diaries” leaves no doubt: this particular trip to hell isn’t worth the scenery.

What ultimately elevates “The Heroin Diaries” above similar confessionals is Sixx’s unflinching self-assessment. He’s not asking for forgiveness or understanding—just documenting his dance with death for anyone who might recognize themselves in his spiral. It’s rock memoir as public service announcement, delivered with the same theatrical flair that made Mötley Crüe impossible to ignore, even at their most appalling.

TATTOOS & TEQUILA: The Memoir No One Asked For (Including Its Author)

If “The Dirt” was Mötley Crüe’s group therapy session and “The Heroin Diaries” was Nikki’s deep dive into personal hell, then “Tattoos & Tequila” is Vince Neil showing up late to his own autobiography, forgetting why he’s there, and then complaining about the accommodations.

Published in 2013 with journalist Mike Sager valiantly attempting to wrangle coherence from chaos, this book is the literary equivalent of being trapped in a limo with a drunk, bitter celebrity who keeps losing his train of thought. The contrast between Sager’s polished introduction and Neil’s subsequent verbal hurricane is so jarring it feels like a practical joke played on readers.

The format—Vince’s rambling monologues interspersed with oral history segments from family, wives, and associates—creates a disjointed experience that mirrors the singer’s famously scattered attention span. Just as you’re following a potentially interesting anecdote about his Compton childhood (complete with a gang member slashing his throat over fifteen cents), Neil veers off into iPhone directions and Google Maps asides that should have been edited out faster than a guitar solo at a punk show.

What emerges between the detours is a portrait of a man who stumbled into rock stardom with all the deliberation of someone tripping over their own shoelaces. Unlike his bandmates who hungered for fame, Neil was recruited primarily for his hair length and popularity with girls—qualifications that apparently proved sufficient for fronting what would become one of rock’s most successful acts.

The book’s most compelling revelations come not from Neil himself but from the supporting cast. His parents gently correct “The Dirt’s” version of events, while his various wives provide insights he seems incapable of articulating. Wife Lia’s casual mention that Neil was on his third facelift by age 48 speaks volumes about insecurities he never acknowledges.

Vince’s bitterness toward his former bandmates permeates the book like cigarette smoke and hairspray. Nikki and Tommy are dismissed as “fame-hungry social climbers” with marginal talent, while Mick is barely acknowledged. (FYI, Mick is the only band member who has not published his memoirs.) The tragic death of Neil’s daughter Skylar becomes a cudgel to beat his former friends with for their lack of support—a grievance somewhat undermined by his admission that he similarly ignored their crises.

The few genuinely entertaining segments—anecdotes about David Lee Roth and Ozzy Osbourne, plus a petty but amusing jab at Tommy Lee’s anatomical boasting—get lost in the narrative wilderness. For instance, Vince proudly points out that it was HIS crotch on the “Too Fast For Love” cover, a flex that might have landed better if the rest of the book displayed similar self-awareness.

Even the publisher seems to have checked out, allowing egregious typos like “balling me out” and “cut and dry” to slip through from a publishing house that has handled authors like Quentin Tarantino and Michael Connelly. It’s as if everyone involved, from writer to editor to proofreader, collectively gave up midway through, mirroring the half-hearted effort that characterizes much of Neil’s post-80s career.

What’s missing from “Tattoos & Tequila” is any meaningful introspection. While Nikki Sixx confronted his demons and Tommy Lee enthusiastically shared his excesses, Vince Neil remains a surface-level narrator of his own life, unwilling or unable to examine what drives him or what it all meant. The result feels less like an autobiography and more like an extended, complaint-filled interview at a bar that’s about to close.

For Crüe completists, the book offers a few new angles on familiar stories, but for the casual reader, it’s the literary equivalent of Neil’s infamous 1992 Indy race—starting with promise, crashing spectacularly, and leaving everyone wondering what the point was in the first place.

Drumroll please… My favorite memoir of the lot is… TOMMYLAND!

Welcome To TOMMYLAND: Where Drumsticks, Libidos, and Regrets Collide

In the pantheon of rock memoirs—which at this point could fill a library wing dedicated to bad decisions and questionable substance intake—“Tommyland” (cowritten with Anthony Bozza) occupies a uniquely tumultuous space. It’s like someone tossed a stack of Polaroids in the air, gathered them in whatever order they landed, and said, “Fuck yeah, that works.”

And somehow, weirdly, it does. Please believe (to quote a particular Tommyism).

Tommy Lee Bass—Athens-born, California-raised, and possessed of a seemingly inexhaustible supply of both energy and poor judgment—invites readers into his world with all the subtlety of a Marshall stack set to 11. His 2004 memoir reads less like a chronological autobiography and more like an extended hangout session with your friend’s wildly entertaining but slightly exhausting uncle who played Lollapalooza and has “stories, man.”

The format itself is a thing of beautiful madness. Chapters careen from topic to topic with the same wild abandon as a Mötley Crüe drum solo. One minute you’re reading about his childhood music lessons, the next you’re deep into his philosophical musings on, well, anything that crosses his mind. And yes, in perhaps the most Tommy Lee move imaginable, his penis occasionally chimes in with its own commentary. If you’ve seen that tape (you know the one), you’re aware this particular member should probably have its own zip code and has earned its speaking privileges through sheer impressive credentials alone.

What emerges through the disorder is a portrait of a man who, despite his best efforts to present himself as rock’s eternal teenager, reveals surprising depth between the lines. The genuine grief over his father’s passing and the palpable anguish surrounding the tragic drowning of a child at his home display a vulnerability that cuts through the “bad boy drummer” persona he’s cultivated for decades.

His reflections on his marriages offer fascinating glimpses into relationships lived under the hot spotlight glare. The Heather Locklear years ended with breathtaking self-sabotage (cheating with a porn actress when your wife is Heather Locklear is a special kind of self-destructive genius). The Pamela Anderson chapters radiate a complex mix of passion, toxicity, and genuine love. Their relationship—punctuated by domesticity, jail time, and that infamous honeymoon video—emerges as rock’s most fascinating car crash, impossible to look away from.

Lee’s talent shines through the chaos—both musical and literary. The man who helped craft some of hair metal’s most explosive anthems clearly possesses an artist’s soul. His co-writer Anthony Bozza deserves medal-worthy recognition for capturing Lee’s voice so perfectly you can practically hear the drumbeat behind every sentence. The writing style mimics the man himself: hyperactive, occasionally profound, frequently hilarious, and utterly incapable of focusing on one topic for more than a few paragraphs.

There’s something refreshingly honest about “Tommyland.” Unlike more polished rock memoirs that either deny responsibility entirely (looking at you, Paul Stanley) or offer carefully managed mea culpas, Lee’s book throws everything at the wall—regrets, triumphs, philosophies, and raunchy anecdotes—with equal enthusiasm. He’s not seeking redemption or crafting a legacy. He’s just showing you his truth, messy as it may be.

Reading “Tommyland” in 2025 offers an additional layer of retrospective irony. Published in 2004, the book predates his 2008 reunion with Pamela, his 2019 marriage to internet personality Brittany Furlan (born roughly when “Dr. Feelgood” was climbing the charts), and numerous other life chapters that would make fascinating additions to this wild tale.

For rock biography enthusiasts, “Tommyland” sits somewhere between Motley Crüe’s group confessional “The Dirt” and a fever dream after binge-watching VH1’s “Behind the Music.” It lacks the methodical chronology of Keith Richards’ “Life” or the poetic gravity of Patti Smith’s “Just Kids,” but it offers something equally valuable: an unfiltered look at a life lived at maximum volume.

Like any good rock show, this book leaves you simultaneously exhausted and exhilarated. You might not understand everything that just happened, but you’re oddly grateful to have been along for the ride. If Tommy Lee’s drumming career had never taken off, he could’ve made a decent living as your most entertaining barstool companion—the guy with stories so wild they strain credulity until you remember who’s telling them.

“Tommyland” is rock memoir as amusement park ride: disorienting, occasionally nauseating, probably not suitable for children, but ultimately a hell of a good time. Just like its author.

= = =

StaciLayneWilson.com

Excellent band . It’s unfair to just list them as hair metal as many do . Another band unfairly snubbed by the Hall of Fame

Great work, Staci! Thank you for such an engaging piece. Tommyland is the only one I haven’t read yet. Looks like I’ll be adding it to the TBR pile.